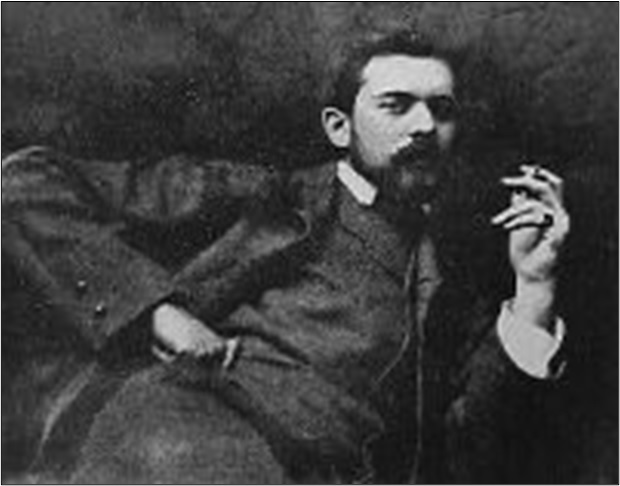

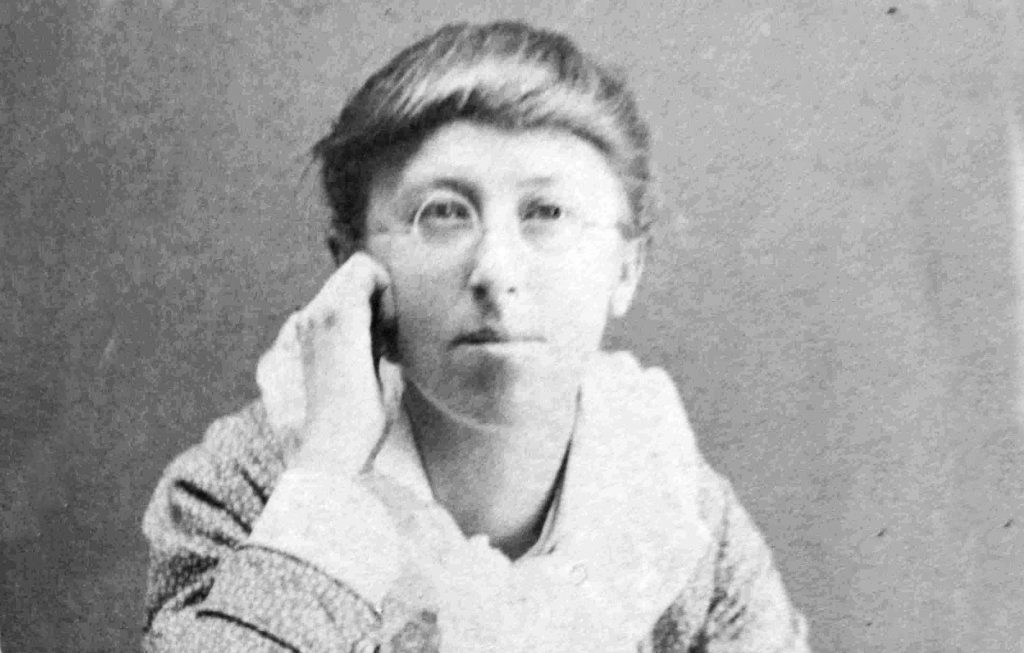

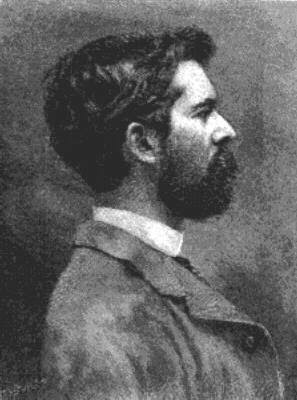

About twenty years ago, I wrote a couple of “cozy village” mysteries, literally set in my own “village” of West Portal in San Francisco, with the emphasis on the intricacies of untraceable poisons and evanescent nanotechnology that required significant outlining, planning ahead and scrupulous, detailed planting of clues as well as red herrings—absolutely a requirement if you’re writing a mystery that is plot-driven and complicated. But then I fell in love—with John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) and his friend Violet Paget (1856-1935, aka the writer Vernon Lee). I wrote an historical novel about him and his magnificent and at the time, maligned, portrait of “Madame X”, and Violet was a significant character in the story (Portraits of an Artist, 2010).

Their individual, quirky, wonderful, interesting personalities, combined with their life-long friendship, made such an impression on me that after the novel was finished, their voices and charming ways would not leave my mind. I had read so many letters of theirs, and biographies, and spent hours gazing at Sargent’s paintings and reading Violet’s essays, that these two fascinating people had a hold on me that compelled me to continue writing about them—I wanted everyone to know them as I had come to know them.

So naturally, I turned them into amateur sleuths and started writing a mystery series! Unlike my West Portal cozies, I wanted these new mysteries to primarily portray the characters of these two real-life people whom I loved so much, in addition to being a good mystery, of course.

Having decided this was going to be a series (and in six years I have now written three), I decided to start when John and Violet were both twenty-one. That way, each book would advance a certain amount of time and I would be able to present the changes and development of the young artist and the young writer as they made their way into the upper echelons of their artistic and literary worlds. Thus, the mysteries that came their way to solve—typically a murder—would serve as the catalyst to delve into and reveal their true characters: how they would react and respond to murder and danger, why they would feel compelled to investigate it, and how their friendship and their unconventional upbringings and education would help or hinder their investigations.

Violet Paget was by far the more pronounced, outgoing, feisty personality of the two, and I chose her voice to tell the stories, in First Person POV. While this has its drawbacks, it makes for a significantly “present” character, as the reader is addressed directly, drawn into her thoughts and fears and doubts, and her sarcastic and irreverent approach to a woman’s life, career and chances of literary success in the late Victorian Age.

Here is how I introduced the series, in the Prologue in the first book, The Spoils of Avalon: Violet is writing in 1926, the year after her friend John died, an event which she feels gives her permission to now finally relate the interesting tales of murder and mayhem in which they were involved:

“Sherlock Holmes isn’t the only one who solves mysteries, you know. In our youth, I and my friend Scamps—more formally known as John Singer Sargent—engaged in a fair amount of sleuthing ourselves.”

She goes on to mention that most of the people involved have also passed on, and then continues:

“Modesty restrains me from naming the one who wields the Sherlockian mind, but let me just say, Scamps made an excellent Watson.”

I wanted to place Violet, with her keen, curious mind and waspish, often self-deprecatory and humorous commentary, at the center of the reader’s journey in this time and space, and as a foil and contrast to Sargent, whose personality was much more reserved, congenial and mellow. As Violet goes on to explain, “Nonetheless, as a detecting duo, we were extremely well-suited—he was observant with an artist’s eye for detail as well as the nuances of mood and tone, whereas I noticed things out of restless curiosity and, I must say, a suspicious nature attuned to finding fault.”

In the first mystery, it becomes rather obvious after a short time who the murderer is, but events occur so quickly, with rising urgency and threat, that the emphasis on Violet’s and John’s rapid detecting is much more interesting and important (if I do say so myself) than that the killer remain unknown until the very end. (The second and third mysteries are rather more complex, partly I think because I’m just getting better at writing mysteries!)

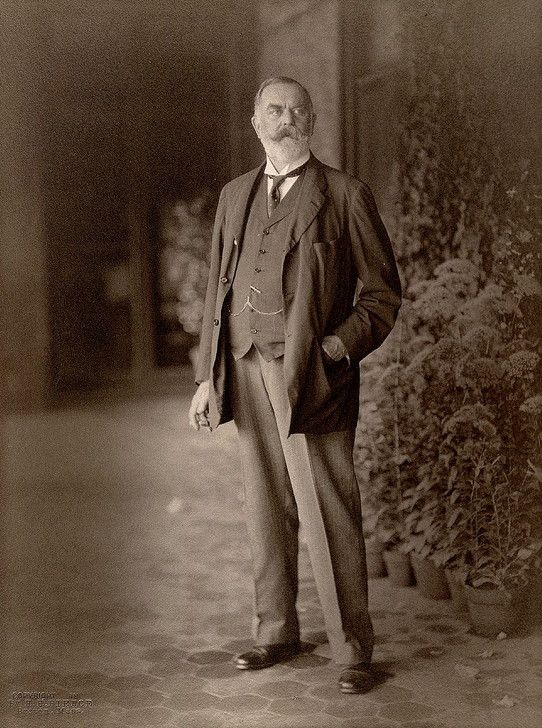

As I mentioned, I read so much of these two persons’ actual correspondence that I have been able to get a true sense of how they spoke, not only to each other, but about events of the day, their opinions, their friendships, successes and failures. John often refers to Vi as “old man”, a common jocularity of the youth of the era, both men and women. Nicknames like “Scamps” were also common among familiars. Sargent was known for his awkwardness in speaking, almost stammering at times, especially in more public situations, whereas Violet was voluble and incessantly talkative, as well as clever and opinionated. Henry James referred to her as a “formidable conversationalist.”

An important element of the lives and personalities of John and Violet was that they were both same-sex oriented; in writing about them I knew that this was a subject that had to be treated with subtlety, for a couple of reasons. First, the self-knowledge of their sexuality would have taken some time, both because of their unusual family lives, insular and peripatetic; and second, because of the mores, strictures and laws of the Victorian Age. Both of them, in later years, were well-acquainted with Oscar Wilde and other notorious gay men of the age—and they saw what happened to him because of his indiscreet behavior. Sargent’s career would have been in ruins if his same-sex inclinations were made public, although as long as men were discreet, nobody cared. Violet, given the separate lives that men and women lived in the Victorian Age, would have had more ‘cover’ for an intimate relationship with a woman friend. The “Boston Marriage”, so-called in the United States, and the necessity of “spinsters” having to live together to make a viable economic household, were too common for anyone to draw anything sexual (or “Sapphic”) from the occurrence. Neither Violet nor John were in any way religious, but social mores would have inhibited behavior that flaunted such activity.

Nonetheless, it has become clear in the scholarship of the last four decades that Sargent was definitely gay and engaged in physical intimacy with other men, from his own letters (not many of which are extant, as he destroyed much of his correspondence, like Henry James) as well as others’ letters and notes about him. The recent exhibition of drawings at the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum of Sargent’s African-American model Thomas McKellar are revelatory of Sargent’s sexual identity. It is less clear whether Violet engaged physically with any of the women with whom she formed relationships in later life, but she certainly preferred the company of women to that of men as intimate companions.

This sense of developing self-awareness is built into my characterizations of John and Violet in the mystery series, and I find it is important to interweave their growing consciousnesses into the stories themselves, which becomes more significant in the latest of the mysteries, The Unicorn in the Mirror, when they are both around twenty-six years of age.

In contrast to my earliest murder mysteries, which were carefully outlined and plotted in advance, my approach to writing about Violet and John’s exploits is more fully organic—once I’ve done the necessary research, I just start writing—their personalities take over pretty quickly, and before I know it, they’re telling me what to write and leading me into all sorts of interesting adventures. I start thinking and feeling like them, especially Violet, and as I work through the investigation along with them, I find out almost at the same time they do, who-done-it and why! Their particular ways of thinking and acting, in their own historical contexts—in short, who they are as persons of their era—have become critical and instrumental elements to solving the murders and crimes they investigate—truly character-driven historical fiction.